Week 2

Gender and Sexuality

Soci—269

Gender and Inequality–

September 8th

Some Reminders

And Some Clarification

Response Memo Deadline

Your first response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM tonight.

Some Reminders

And Some Clarification

You are, of course, free to “skip” one week (i.e., by not submitting a memo) without incurring a penalty.

Some Reminders

And Some Clarification

How should you … well, “read” or navigate

our course readings?

Some Reminders

And Some Clarification

Gender and Inequality–

Measurement

A Group Exercise

Get into groups of 2-3 students. Think about gender inequality. Propose one basic theory of how gendered disparities emerge and endure. How could you test your theory using quantitative tools?

Think broadly here: e.g., how would you measure constructs like

gender and inequality?

Gender Stereotypes and Education in Print Media

(Boutyline, Arseniev-Koehler, and Cornell 2023)

The Entry Point

Despite the wealth of recent work illustrating the importance of gender stereotypes for academic outcomes, we know little about whether and how these stereotypes changed as gender differences in educational attainment drastically transformed since the 1940s.

(Boutyline et al. 2023:264, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Entry Point

While men reached higher levels of education than women for much of the 20th century, in recent decades this gender gap reversed, with women’s educational attainment increasingly surpassing men’s … These changes in the educational landscape present a rare opportunity to examine how stereotypes change alongside the reversal of a core pattern of stratification.

(Boutyline et al. 2023:264, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Topline Findings

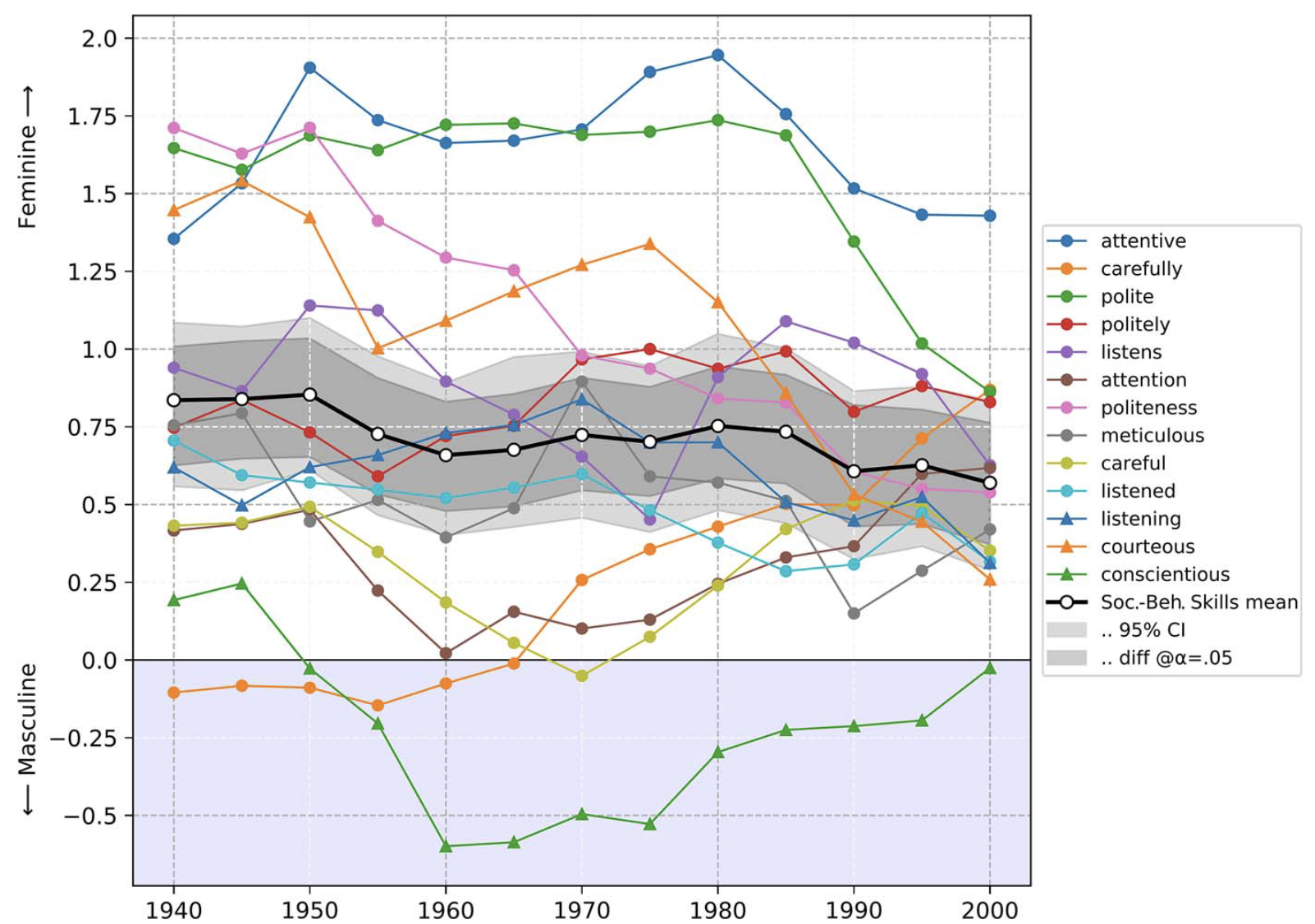

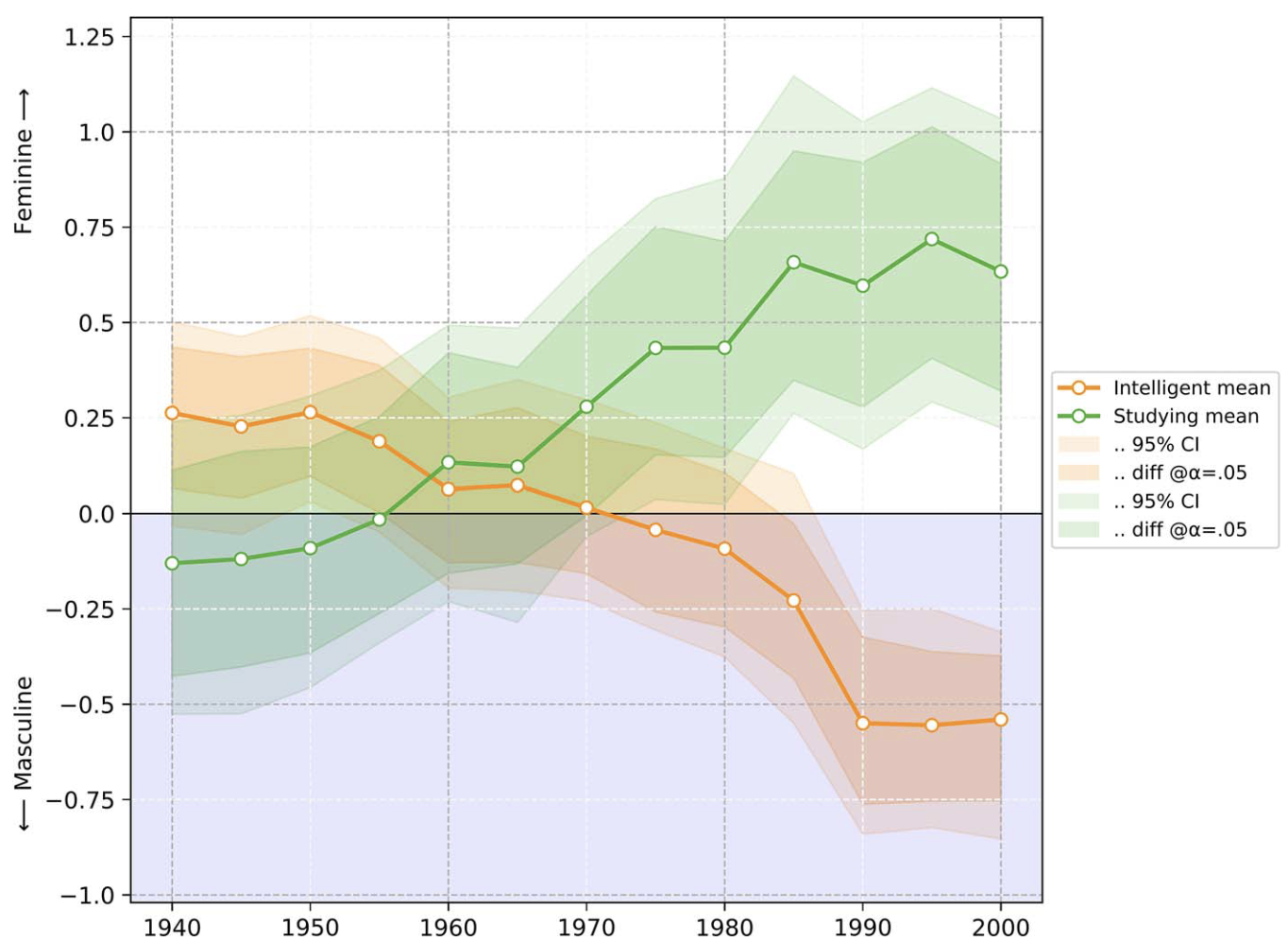

We examined six sets of gender associations that prior work linked to educational outcomes. We found that the stereotypes of socio-behavioral skills and problem behaviors remained unchanged since the middle of the 20th century. The other four stereotypes underwent dramatic changes, with schooling and school effort gaining substantial associations with femininity, and intelligence and unintelligence with masculinity.

(Boutyline et al. 2023:278, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Topline Findings

Figure 3 from Boutyline and colleagues (2023)

Topline Findings

Figure 8 from Boutyline and colleagues (2023)

Let’s Work Backwards

Gender Stereotypes

Two Orienting Questions

What are gender stereotypes?

What are hegemonic gender stereotypes?

How Do Stereotypes Change?

Social role theory … argue(s) that popular gender stereotypes are updated to reflect the different roles that men and women tend to occupy in society, and to ascribe men and women characteristics consistent with these roles … [W]e reason that the widespread, thoroughgoing changes in women’s relative educational attainment across the 20th century should have resulted in updates to popularly held stereotypes, with stereotypes of women altered to include more of the traits and behavior believed to be important for educational success.

(Boutyline et al. 2023:265–66, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Six Stereotypes Under Evaluation

Schooling and School Effort

Socio-Behavioural Skills and Problem Behaviours

Intelligence and Unintelligence

Group Exercise

Meaning in Words

In groups of 2-3, discuss the following items:

Why do the authors think that some gendered stereotypes have endured while others have acquired new gendered valences?

How did the authors test their claims in the empirical arena? This does not, of course, have to be technically “correct.”

Money, Birth, Gender

(Machado and Jaspers 2023)

The Central Puzzle

A Question

In Money, Birth, and Gender, what are Machado and Jaspers (2023)trying to make sense of?

The Central Puzzle

Why earnings trajectories following parenthood are unequal

among different-sex couples.

“A substantial body of research shows that the birth of a child increases inequality within different-sex couples, as mothers bear the brunt of unpaid work and face penalties in the labor market, whereas fathers’ careers are barely affected and might even benefit from a premium.”

(Machado and Jaspers 2023:429, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Another Question

What explains these disparities?Potential Mechanisms

Money

Birth

Gender

Potential Mechanisms

[F]athers have, on average, higher pre-parenthood earnings than mothers, so the gender divergence in earnings trajectories might be due to couples maximizing their joint income by “efficiently” specializing, that is, having the partner who makes less money do a larger share of unpaid work.

(Machado and Jaspers 2023:429, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The biological circumstances of childbearing might provide practical and symbolic bases for the unequal work–care practices that shape diverging earnings trajectories.

(Machado and Jaspers 2023:429–30, EMPHASIS ADDED)

[T]he increase in inequality might result from couples performing and affirming gender differences through the division of paid and unpaid labor.

(Machado and Jaspers 2023:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

In other words, couples may be doing gender.

Click for More Context

According to this theory … [w]omen … spend more time on housework and less time on paid labor as an act of “doing gender”: women, as well as the broader society, view domestic labor as an act that affirms femininity, and acting in accordance with gender norms comes with the rewards of fitting in.

(Jaspers, Mazrekaj, and Machado 2024:519, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Another Group Exercise

Potential Mechanisms

In groups of 2-3, discuss why Machado and Jaspers (2023) posit that money, birth and gender represent three “inequality-generating mechanisms” that are, in principle, difficult

to empirically disentangle.

Then, identify how the authors go about

disentangling the mechanisms.

A High-Level Summary

Variation in Couple Type

| Different-Sex Couple, Biological Child | Female Same-Sex Couple, Biological Child | Different-Sex Couple, Adopted Child | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Different-Sex Couple, Biological Child | — | Birth | Gender |

| Female Same-Sex Couple, Biological Child | Birth | — | No Overlap |

| Different-Sex Couple, Adopted Child | Gender | No Overlap | — |

A Question

Why is there no Money mechanism highlighted in the table?Variation in Couple Type

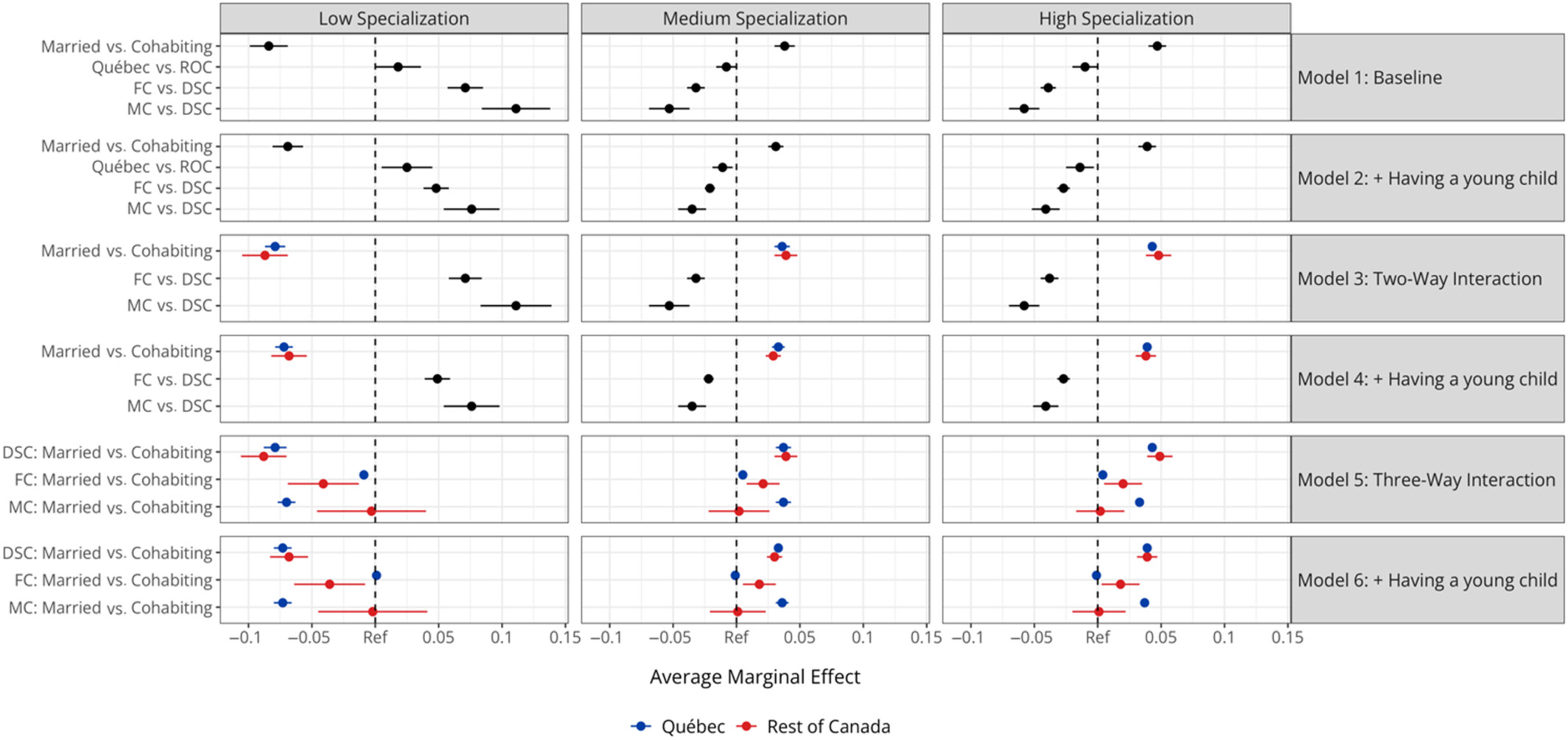

Our results offer strong support for the doing gender hypothesis (H_3). Not only is the key prediction of this hypothesis—that the child penalty would be stronger for mothers in different-sex couples than for birth mothers in same-sex couples— confirmed, but all relevant comparisons point to gender being the overwhelming source of within-couple inequality following parenthood. Birth mothers in same-sex couples have a weaker penalty than birth mothers partnered with men, even though the two groups have the same leave rights and, in the matched sample, are very similar in pre-parenthood characteristics. The comparison between the partners of these two groups of women is also revealing: even when matched on relevant attributes, they have diverging trajectories, as social mothers pay a parenthood penalty but fathers do not.

(Machado and Jaspers 2023:447–48, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Variation in Couple Type

Institutional Context Matters

Figure 1 from Yang (2025)

Sexuality & Gender Identity–

September 10th

First, Some Broad Thoughts

How can you participate in this class?

First, Some Broad Thoughts

Some readings may be easy to understand,

others less so.

First, Some Broad Thoughts

Finally, one last note about

Boutyline et al.’s (2023) findings.

A Group Exercise

The Implications of Abortion Access

In groups of 2-3, put Machado and Jaspers’ (2023) paper on money, birth and gender into dialogue with Everett and Taylor (2024) article on abortion and women’s socioeconomic futures.

Then, discuss how Everett and Taylor’s (2024) motivate (or justify the sociological significance of) their analyses, before mapping

how they test their guiding assumptions.

The Education of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual America

(Mittleman 2022)

Setting the Stage

The “rise of women” in education is among the central demographic transformations of the past half century … [T]he “new gender gap” in education is defined primarily with reference to “boys’ notorious underperformance” … This “problem with boys” has attracted the attention of scholars, policymakers, and the popular press.

(Mittleman 2022:303, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Setting the Stage

In explaining these patterns, sociologists have emphasized the social dynamics of gender over and above the purported dictates of sex. The gender gap, sociologists show, is not an immutable fact of biology; it is a contingent product of students’ social positions and social contexts. To illustrate this fact, stratification research has uncovered considerable heterogeneity in men’s and women’s academic outcomes … Within this body of research, one central axis of inequality has gone largely unobserved: sexuality.

(Mittleman 2022:304, EMPHASIS ADDED)

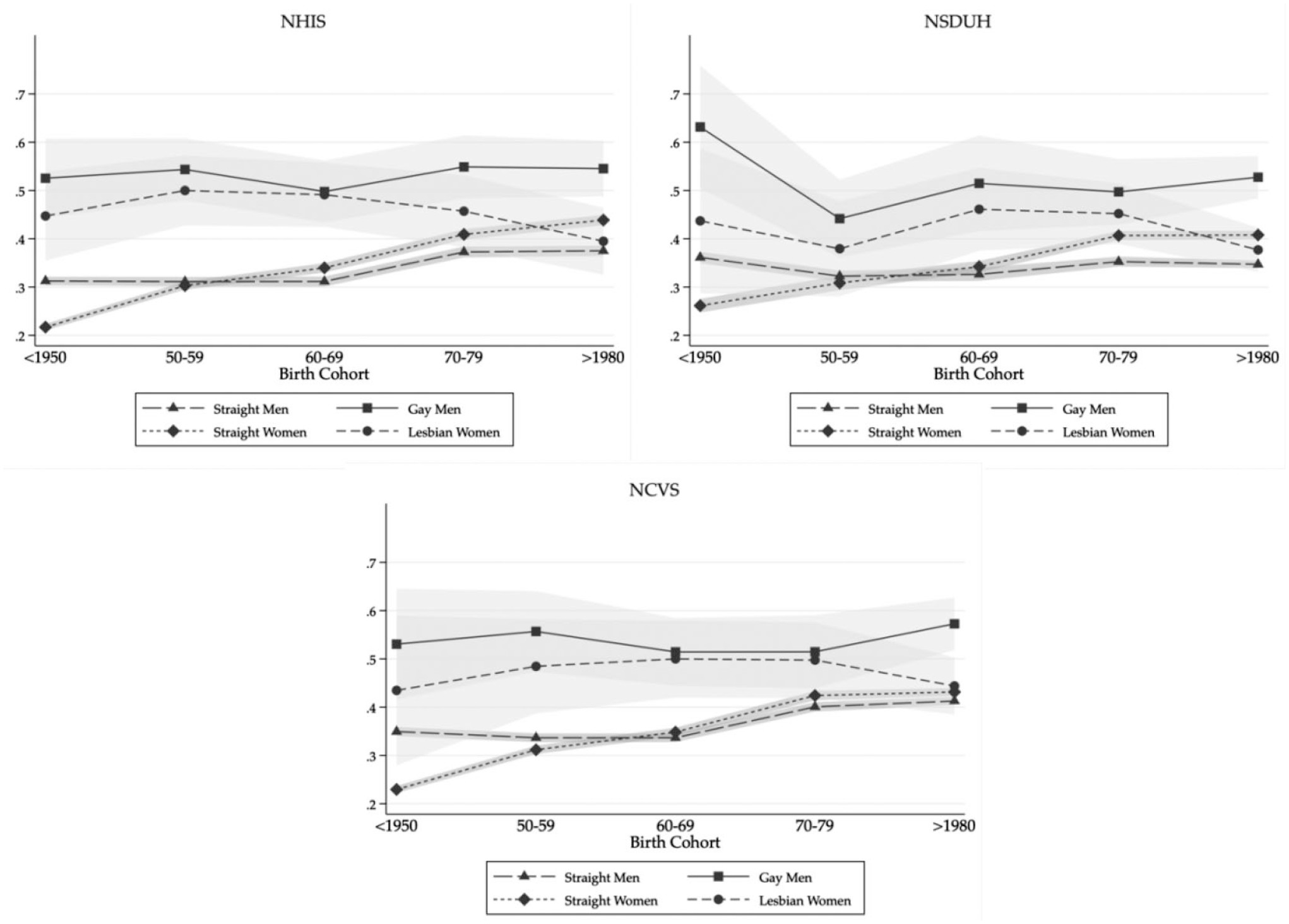

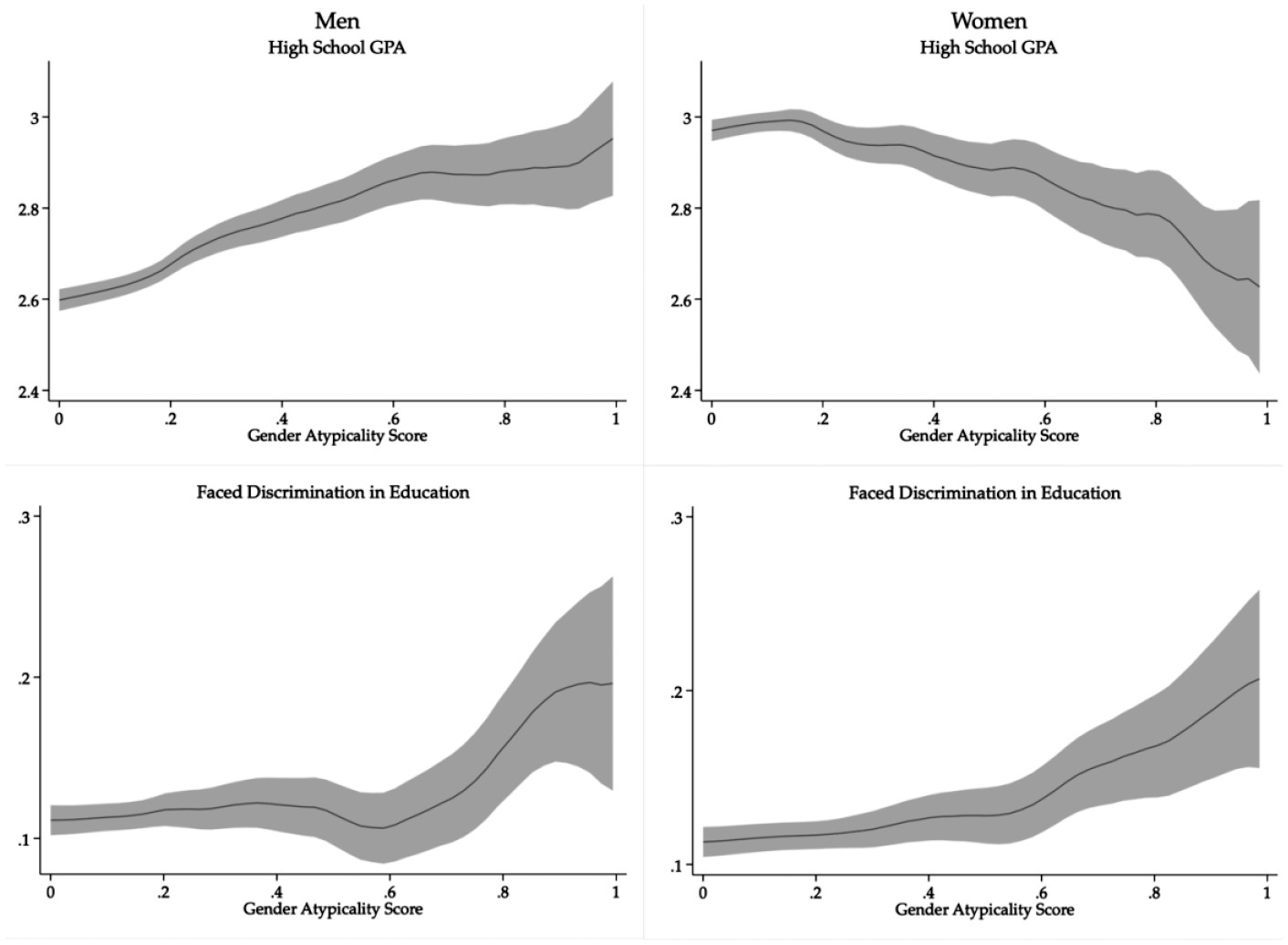

The Key Findings

Across datasets and outcomes, I find consistent evidence that sexuality is a highly consequential axis of academic inequality, albeit in ways that vary sharply by sex. As a whole, my results reveal two core demographic facts. First, “the rise of women” should be understood more precisely as the rise of straight women. Second, “the problem with boys” obscures one group with rather remarkable levels of academic success: gay boys.

(Mittleman 2022:304, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Key Findings

Figure 4 from Mittleman (2022).

The Key Findings

Figure 8 from Mittleman (2022).

Yet Another Group Exercise

Making Sense of the Results

In groups of 2-3, discuss how Mittleman (2022) invokes ideas related to the asymmetric gender revolution, masculinities in the classroom, femininity premiums and bad girl penalties (among other theoretical frameworks) to motivate his analyses.

Then, discuss what the gender predictive approach entails. How does Mittleman (2022) use this approach to adjudicate his central claims?

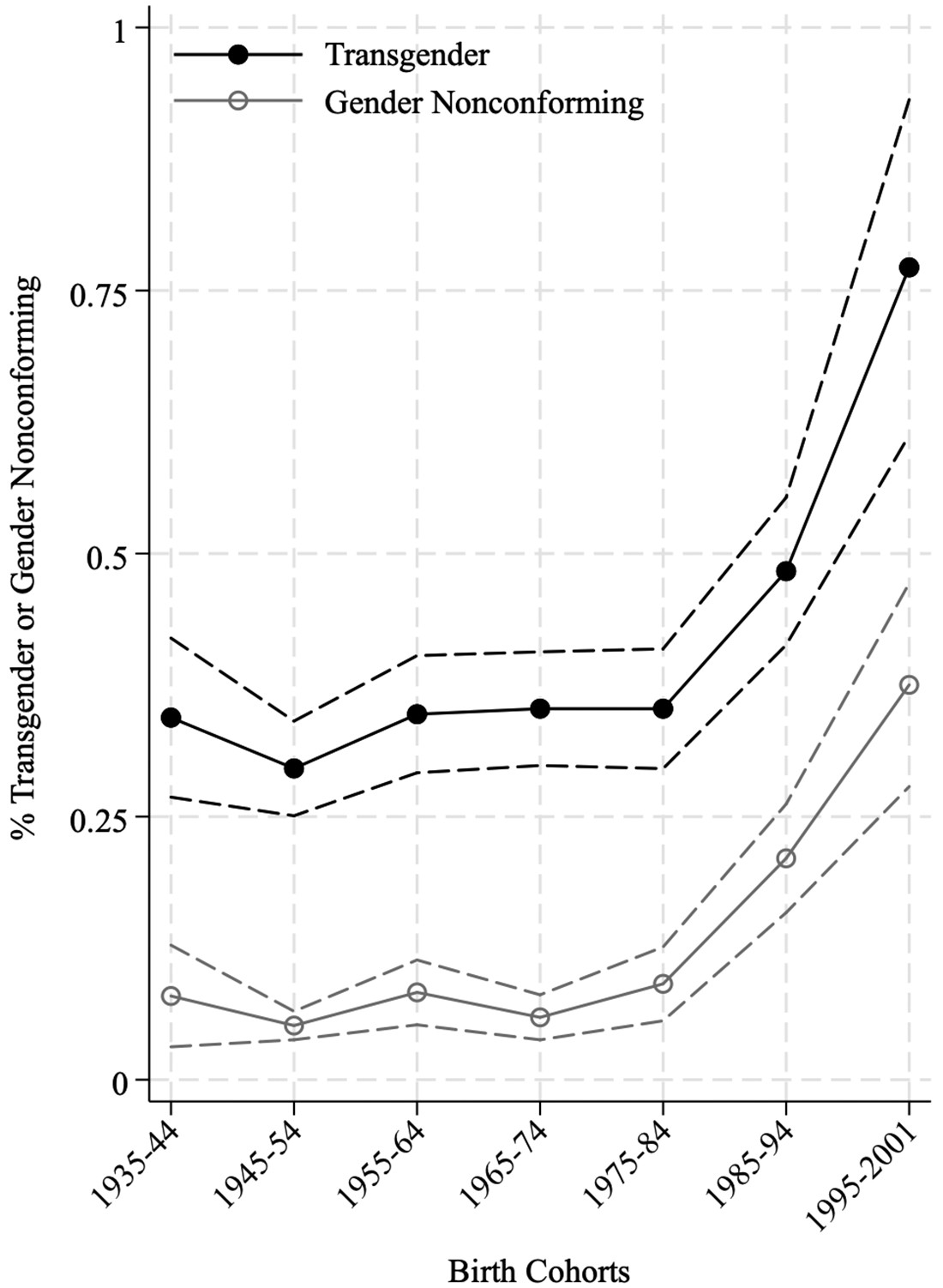

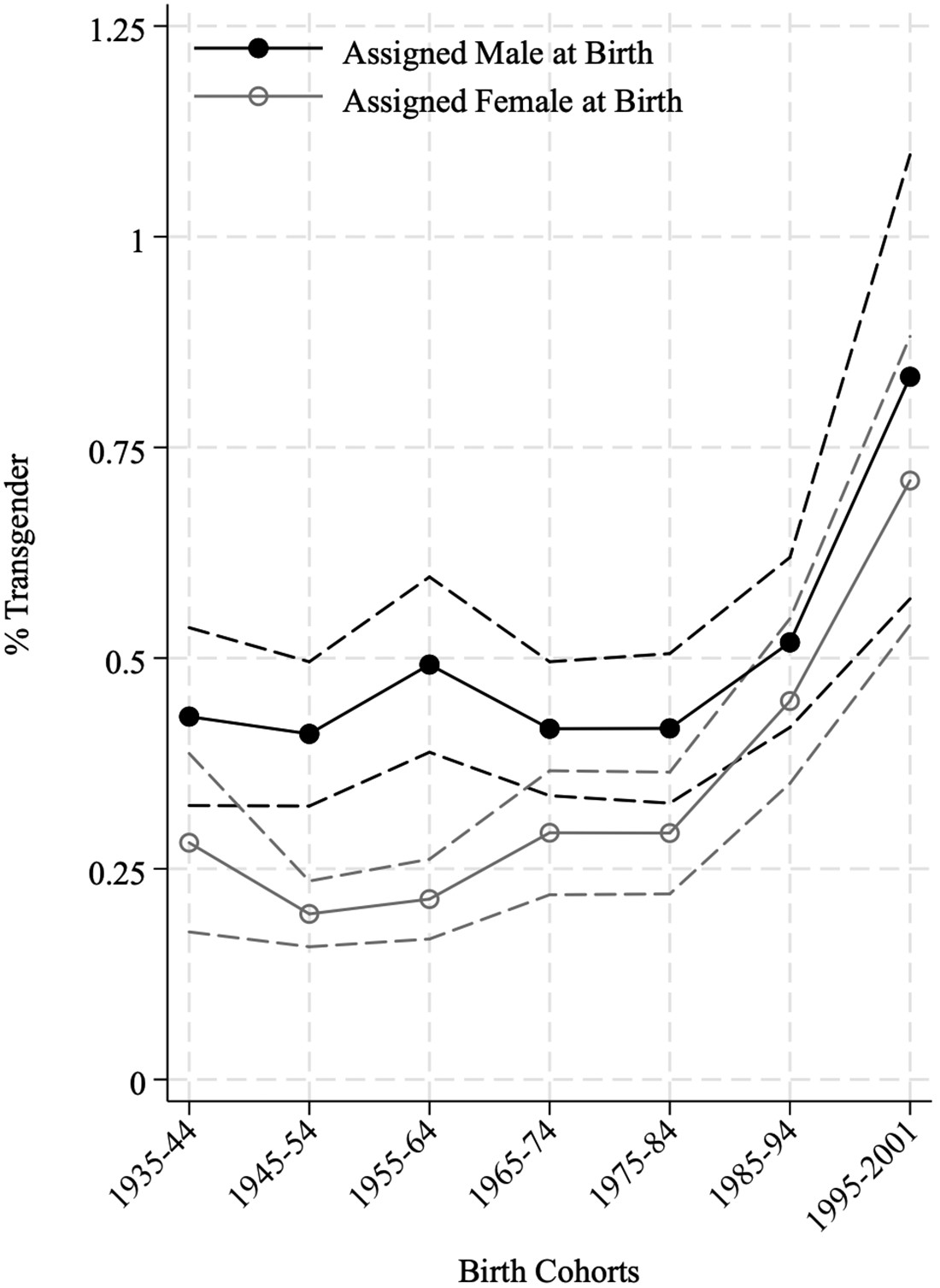

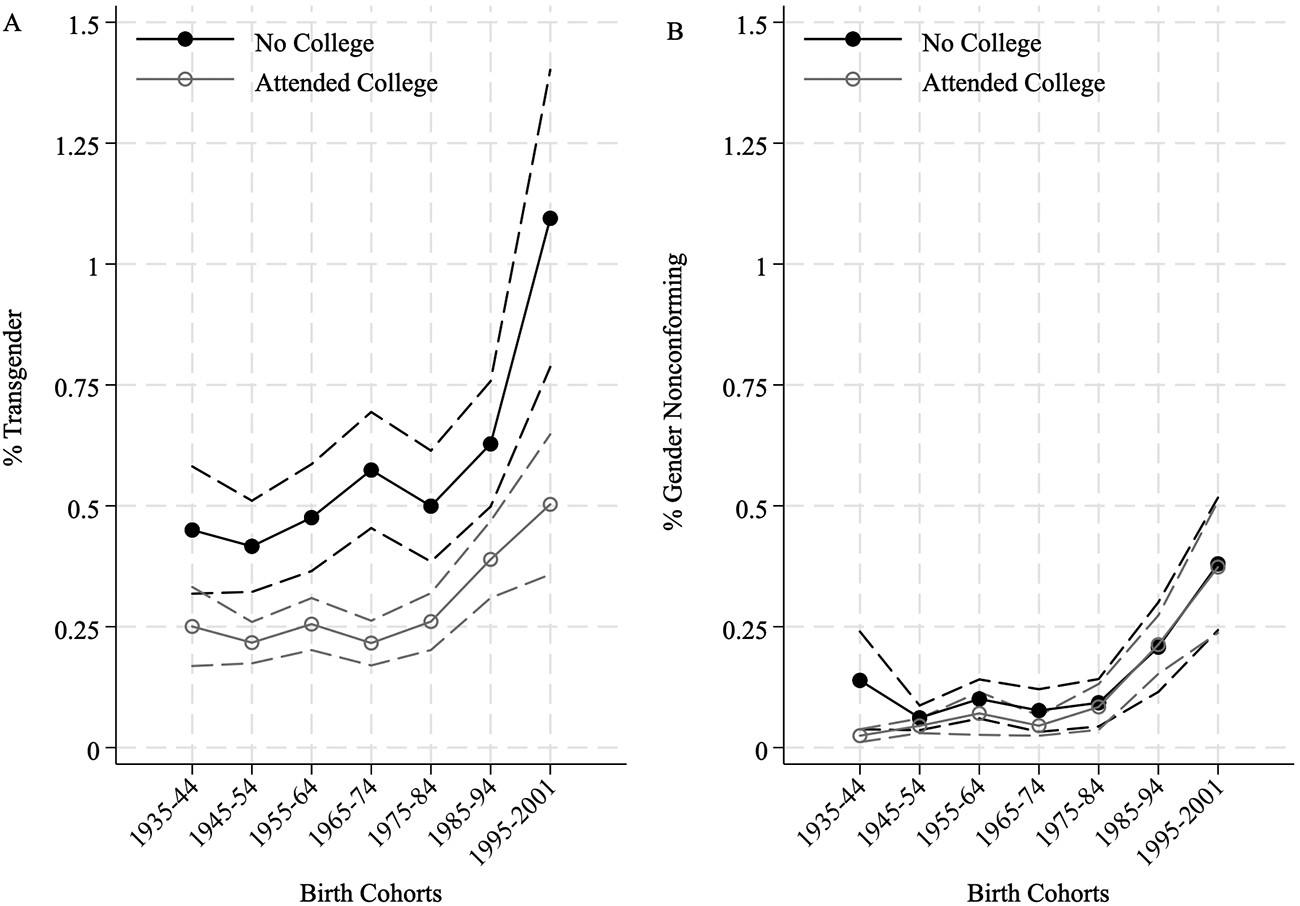

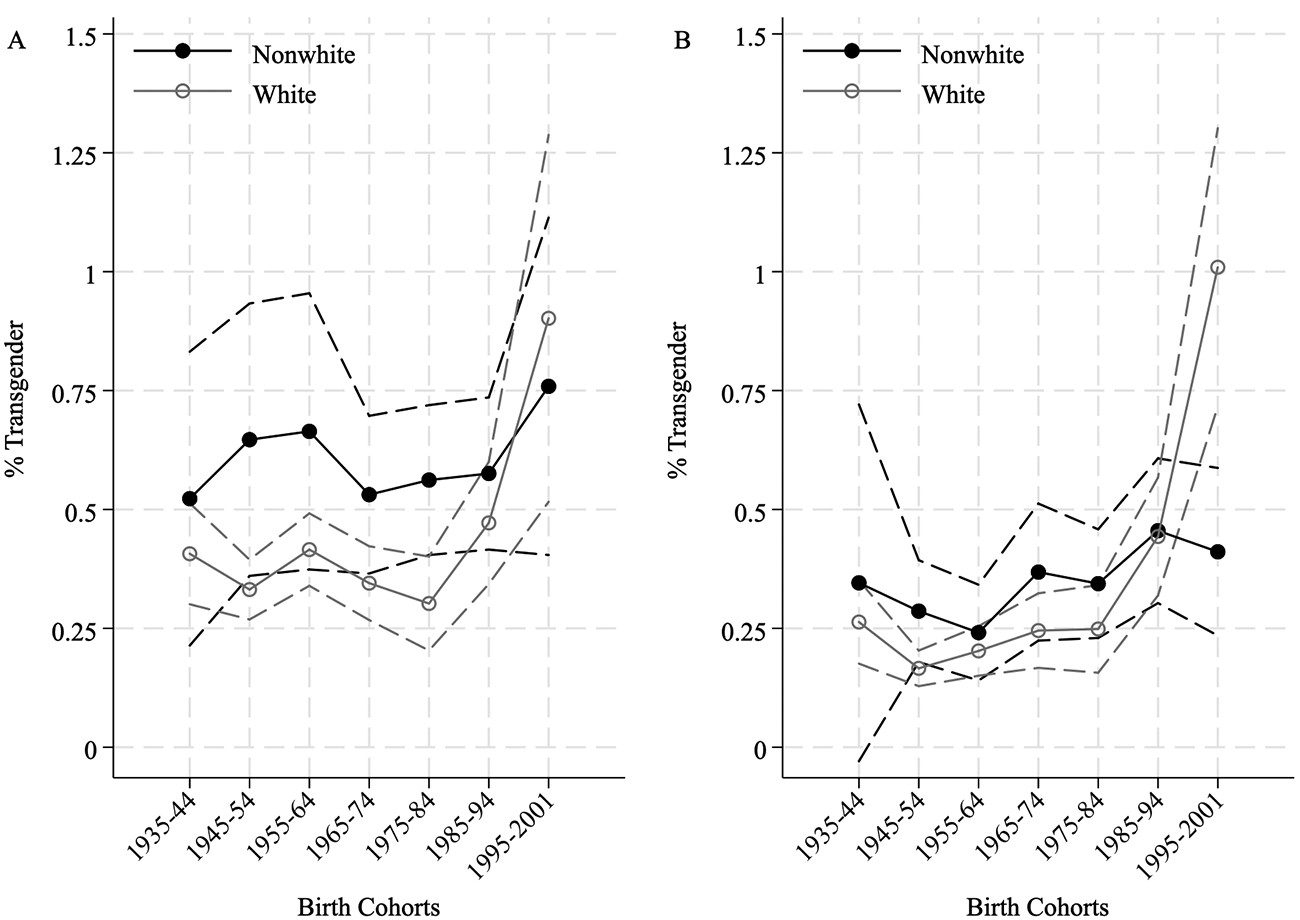

Transgender Tipping Point?

(Lagos 2022)

The Evolving Context

While assessments made by popular media may not always map accurately to periods of social change, historians, sociologists, and other scholars in transgender studies have tended to agree that transgender visibility and civil rights activism increased dramatically at some point in the mid-2010s.

(Lagos 2022:95, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Evolving Context

This potential change in the distribution of gender itself may also intersect with the unequal distributions of outcomes and opportunities along other social dimensions. High-profile developments in transgender visibility and rights associated with the transgender tipping point have had uneven social salience along lines of race/ethnicity and class … Furthermore, there is uncertainty about whether the overall gains associated with this potentially singular tipping point will continue to accumulate, stall, or be rolled back due to changing political contingencies.

(Lagos 2022:95, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Select Findings

Figure 2 from Lagos (2022).

Select Findings

Figure 3 from Lagos (2022).

Select Findings

Figure 5 from Lagos (2022).

Select Findings

Figure 6 from Lagos (2022).

A Final Group Exercise

Accounting for Sexuality

Beyond the normative benefits, what are the analytical affordances of making sexuality and gender identity visible in sociological research?

Discuss in groups of 2-3 students.

See You Monday

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography